Bewick on my knee

To celebrate our 150th newsletter -- Readers, we thank you! -- we think about places people read, beginning with a famed episode from Jane Eyre

A breakfast-room adjoined the drawing-room, I slipped in there. It contained a bookcase: I soon possessed myself of a volume, taking care that it should be one stored with pictures. I mounted into the window-seat: gathering up my feet, I sat cross-legged, like a Turk; and, having drawn the red moreen curtain nearly close, I was shrined in double retirement.

Folds of scarlet drapery shut in my view to the right hand; to the left were the clear panes of glass, protecting, but not separating me from the drear November day. At intervals, while turning over the leaves of my book, I studied the aspect of that winter afternoon. Afar, it offered a pale blank of mist and cloud; near a scene of wet lawn and storm-beat shrub, with ceaseless rain sweeping away wildly before a long and lamentable blast.

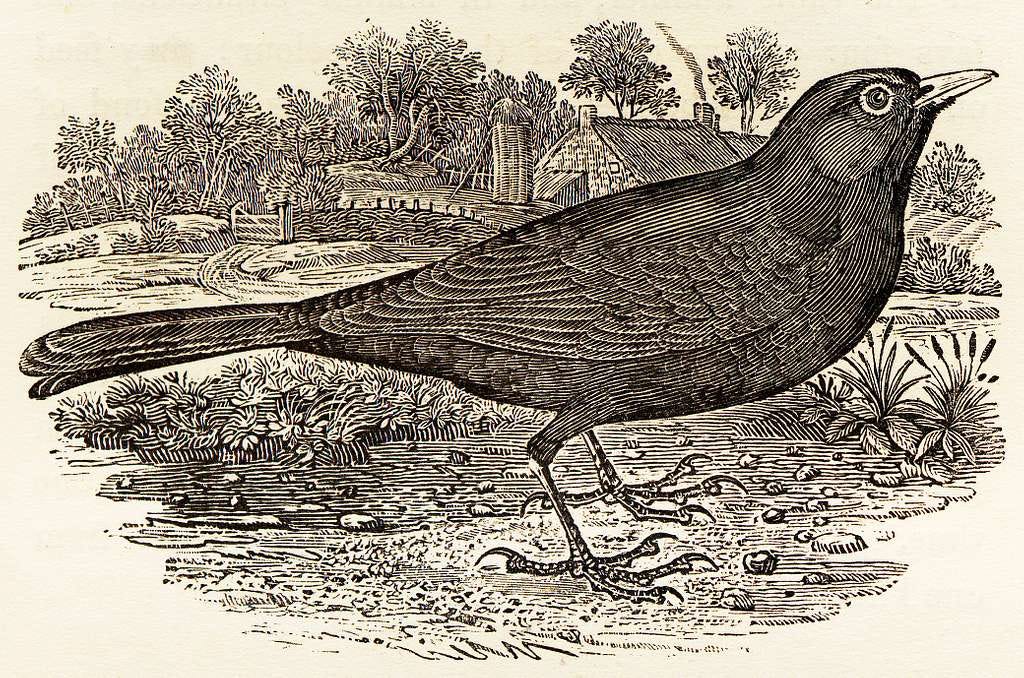

I returned to my book—Bewick’s History of British Birds: the letterpress thereof I cared little for, generally speaking; and yet there were certain introductory pages that, child as I was, I could not pass quite as a blank. They were those which treat of the haunts of sea-fowl; of “the solitary rocks and promontories” by them only inhabited; of the coast of Norway, studded with isles from its southern extremity, the Lindeness, or Naze, to the North Cape—

“Where the Northern Ocean, in vast whirls,

Boils round the naked, melancholy isles

Of farthest Thule; and the Atlantic surge

Pours in among the stormy Hebrides.”

Nor could I pass unnoticed the suggestion of the bleak shores of Lapland, Siberia, Spitzbergen, Nova Zembla, Iceland, Greenland, with “the vast sweep of the Arctic Zone, and those forlorn regions of dreary space,—that reservoir of frost and snow, where firm fields of ice, the accumulation of centuries of winters, glazed in Alpine heights above heights, surround the pole, and concentre the multiplied rigours of extreme cold.” Of these death-white realms I formed an idea of my own: shadowy, like all the half-comprehended notions that float dim through children’s brains, but strangely impressive. The words in these introductory pages connected themselves with the succeeding vignettes, and gave significance to the rock standing up alone in a sea of billow and spray; to the broken boat stranded on a desolate coast; to the cold and ghastly moon glancing through bars of cloud at a wreck just sinking.

I cannot tell what sentiment haunted the quite solitary churchyard, with its inscribed headstone; its gate, its two trees, its low horizon, girdled by a broken wall, and its newly-risen crescent, attesting the hour of eventide.

The two ships becalmed on a torpid sea, I believed to be marine phantoms.

The fiend pinning down the thief’s pack behind him, I passed over quickly: it was an object of terror.

So was the black horned thing seated aloof on a rock, surveying a distant crowd surrounding a gallows.

Each picture told a story; mysterious often to my undeveloped understanding and imperfect feelings, yet ever profoundly interesting: as interesting as the tales Bessie sometimes narrated on winter evenings, when she chanced to be in good humour; and when, having brought her ironing-table to the nursery hearth, she allowed us to sit about it, and while she got up Mrs. Reed’s lace frills, and crimped her nightcap borders, fed our eager attention with passages of love and adventure taken from old fairy tales and other ballads; or (as at a later period I discovered) from the pages of Pamela, and Henry, Earl of Moreland.

With Bewick on my knee, I was then happy: happy at least in my way. I feared nothing but interruption, and that came too soon. The breakfast-room door opened.

About the Author

Charlotte Brontë (1816-55) grew up storytelling with her siblings, Emily, Anne, and Branwell, each encouraging the others in their literary pursuits. You can read more about them here. Charlotte survived a few years more after her siblings succumbed to tuberculosis. Jane Eyre was published under the pen name ‘Currer Bell’ in 1847.

What We Love About This…

Jane, a lonely child here, reads alongside the weather. Her reading is at once a protective enclosure and at the same time a portal and an escape. She overlays herself with different imagined places from her reading, especially a frozen Northern coast, part real and part mythologised. Bronte deliberately chooses a text that would be familiar to many households, Thomas Bewick’s highly popular illustrated natural history, as well known for its engravings as its text to many nineteenth-century children.

Blending her reading of images, memories of fireside stories, and the text, young Jane with ‘Bewick on her knee’ traverses scenes of cold and dark omen with exhilaration. She admits, with the careful restraint of one who is constantly on guard, the precious and particular happiness of her childhood reading. The subsequent ‘red room’ scene, where Jane is punished for retaliating against her bullying cousin, is famous for terror and ghoulish apparitions that might have come from the pages she reads in Bewick’s History (the horned bird overlooking the gallows, perhaps). Yet there is also something else at work here beyond imagery and atmosphere. She is lifted out into the time and place of other worlds, yet these brief moments themselves underpin the bravery and resistance of Jane’s adulthood, equipping her with the capacity to imagine and so embody alternatives to the conditions that are forced on her. Reading for escapism is far from the idle pleasure that phrase usually implies, but a fundamental component in how Jane navigates and impacts her world.

To Read Alongside…

We have written before about Jane Eyre—have a look at our sister-project The Ten Minute Book Club, or TMBC, which features ‘The Red Room’ episode in Chapter two, introduced by Dr Ushashi Dasgupta. In a previous LitHits newsletter on Jane Eyre, we wrote about Jane’s inner struggle to fit in to social expectations of women at the time, which you can read here.

Today’s text features a young girl with a book, magically whisked away from her sorrows by the worlds that it opens up to her. This is a key theme of many contemporary writers, including Katherine Rundell and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Listen to Rundell talk about this important function of children’s books in her series on children’s literature for BBC radio 4. She touches on the importance of reading for enabling children to travel to other worlds, and also how crucial it is that they see themselves in those stories. Adichie’s TED talk on ‘the danger of a single story’ digs deeply into this theme, as she shares her own experiences of being a young girl reading Western literature in Nigeria and gradually realizing that there are other stories to be told.

Suggest a LitHit!

Tell us your own favourites from literature you've read, and we can feature you as a Guest Curator. Just email us with the following information:

Your full name

The title of the book you're suggesting

The location of the excerpt within the book (e.g., "in the middle of chapter 5"), or the excerpt itself copied into the email or attached to it (in Word)

Why you love it, in just a few sentences

**Please note that we welcome all suggestions but at the moment we can only release excerpts that are out of copyright and in the public domain. This usually means 75 years or more since the author's death. You can find many such out-of-copyright texts on the internet, for example at Project Gutenberg and Standard Ebooks.

About LitHits

LitHits helps you make time for reading by bringing you unabridged excerpts from brilliant literature that you can read on the go, anytime or any place. Our curators carefully select and frame each excerpt so that you can dive right in. We are more than a book recommendation site: we connect you with powerful, enduring pieces of literature, served directly to your mobile phone, tablet or computer.

You might also enjoy...

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on our newsletter: kshepherdb@yahoo.co.uk

Graphic design by Sara Azmy

All curation content © 2024 LitHits. All rights reserved.