'A live coal in the sea'

Can sins be redeemed? In this late medieval dream vision, personifications of the Seven Deadly Sins attend Confession, guided by Reason and Repentance--but are their confessions sincere?

From William Langland, Piers Plowman (Passus V)

The story so far: Sir Harvey, the hollow-cheeked personification of Covetousness (Greed), confesses to Repentance that he has been engaging in lies, ‘wicked weighing’, usury, and miserly hoarding, pursuing every exploitative scheme he can to increase his wealth. Adapted from the Harvard Chaucer translation (below), Middle English spelling has been modernised for readability.

Now read on:

Repentance:

‘Have you pity on poor men · that must needs borrow?'

Covetousness:

'I have as much pity on poor men · as has a pedlar of cats

He would kill if he could · for the sake of their skins.'

Repentance:

'Art thou generous to thy neighbours · with thy meat and drink?'

Covetousness:

'I am regarded as kind · as a hound in the kitchen;

Among my neighbours especially · I have such a name.'

Repentance:

'Now God never grant thee · (but thou soon repent),

His grace on this ground · thy goods well to bestow,

Nor thine heirs after thee · to have joy of thy winnings,

Nor executors spend well · the silver thou leavest;

That which by wrong was won · by wicked men to be spent.

For were I friar of that house · where is good faith and charity,

I'd not clothe us with thy cash · nor our church amend,

Nor have for our pittance · penn'orth of thine

For the best book in our house · though bright gold were its leaves,

If I knew indeed · thou wert such as thou tellest,

Or if I could know it · in any sure way.

Servus es alterius cum fercula pinguia quaeris,

Pane tuo potius vescere, liber eris.

[Unknown source: Seek costly foods, another’s slave you’ll be, but eat your own plain bread and you will stay free]

Thou art an unkindly creature · I cannot absolve thee

Till thou make restitution · reckon up with them all;

And till Reason enrol · in the register of Heaven

That thou hast made each man good · I may not absolve thee --

Non dimittitur peccatum, donec restituatur oblatum, etc.

[Augustine Epistle 153.20: The sin is not forgiven until the stolen goods are returned]

For all that have aught of thy goods · so God have my truth!

Will be held at the high Day of Doom · to help thee to restore.

And whoso believeth not this · let him look in the Psalter,

In Miserere mei Deus · whether I speak truth;

Ecce enim veritatem dilexisti, etc.

[Psalm 50.3: Have Mercy on me, O God; For behold thou hast loved truth…]

Shall never workman in this world · thrive with what thou winnest;

Cum sancto Sanctus eris · construe me that in English.'

Then drooped the scamp in despair · and would have himself hanged,

Had not Repentance the rather · recomforted him in this manner,

'Have mercy in thy mind · and with thy mouth ask it,

For God his mercy is more · than all his other works;

Misericordia ejus super omnia opera ejus, etc.

[Psalm 17.26: With the holy thou wilt be holy; Psalm 144.9: His tender mercies are all over his works]

And all the wickedness in this world · that man might work or think

Is no more to the mercy of God · than a live coal in the sea.

What we love about this…

Madeleine L’Engle, author of the widely loved book A Wrinkle in Time, borrowed from this passage for the title of her novel A Live Coal in the Sea.

Repentance is very clear that these wicked earnings are dirty money that cannot be used for any good but restitution. Nonetheless he means by this image that the vast depths of God’s mercy will swallow up all manner of sin, if the one who committed those evils repents, which is in line with late medieval Christian belief in the importance of confession. But it’s a striking image—what actually happens to a live coal when it’s submerged in sea water? Does it stay hot, or die out immediately? Does it fizzle and bubble, does it give off steam or smoke? What kind of metaphor is it?

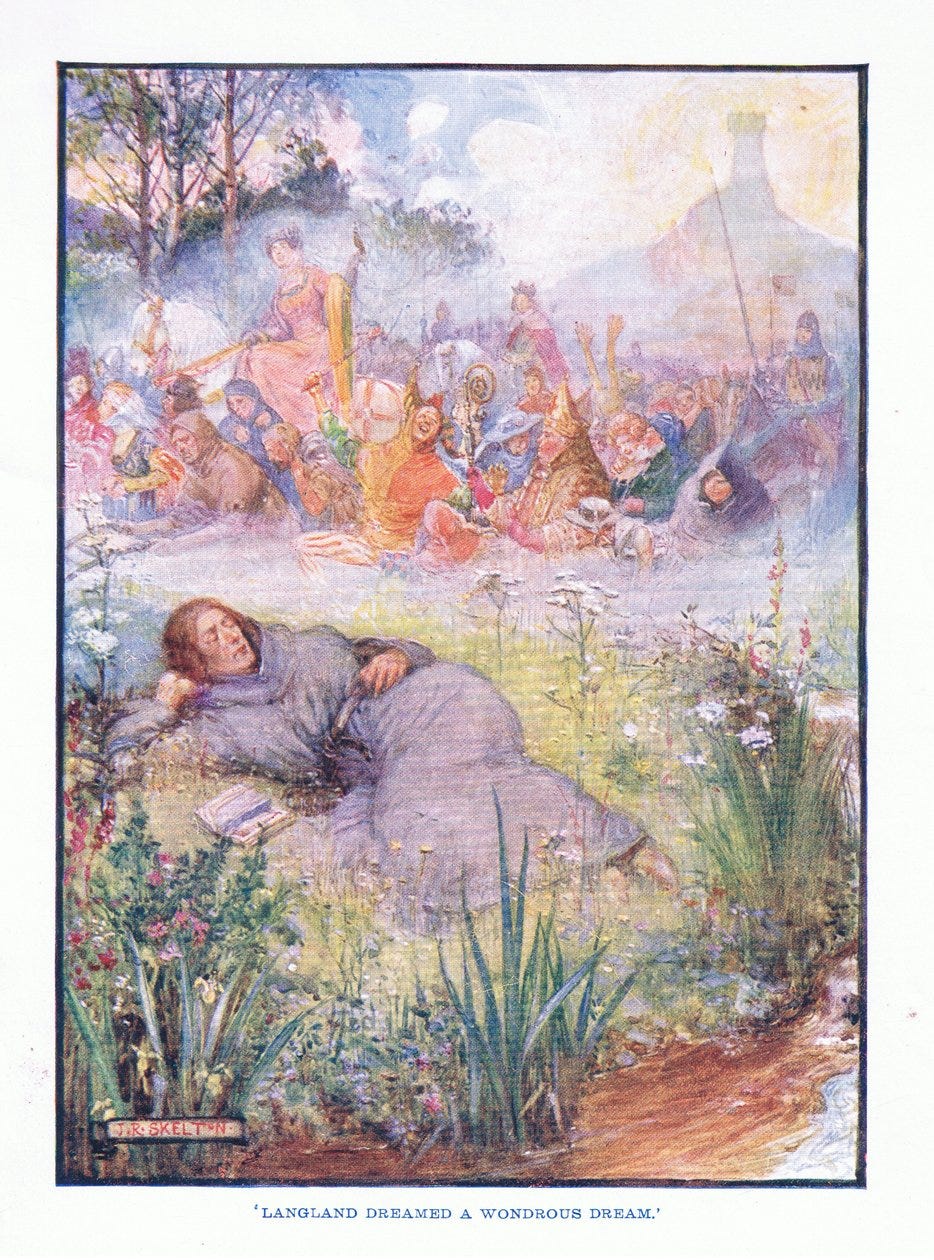

And how does sleep come into it? Will, the dreamer of Langland’s poem, falls asleep outdoors, in the Malvern Hills in England, experiencing his vast vision of the ills and cures for society. In the history of literary fiction, sleep often initiates extraordinary adventures—especially sleeping in the open air. Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland opens with the young Alice snoozing by a riverbank and finding herself plunging down a rabbit hole to a land of incredible creatures and experiences. In an earlier tale, Washington Irving’s ‘Rip Van Winkle,’ Rip falls asleep in the Catskill Mountains after some strong drink and wakes up twenty years later, having entirely missed the American Revolutionary War.

About the Author

William Langland (c.1332(?)-c.1400(?)) is a fourteenth-century poet who wrote the influential and popular alliterative poem, The Vision of Piers Plowman, which survives in over 50 manuscripts and 3-4 versions, as Langland revised the poem during his lifetime. As Langland tells us in the C-text of his poem that he was born near Malvern and educated for a career in the Church, but worked for most of his later life as a psalter-clerk in London. He might also have been very tall, or as he puts it, ‘long’. Piers Plowman was his major work, which he wrote and revised from c.1360 until the time of his death. He might also be identified as the author of ‘Richard the Redeless’. Read more about Langland on our Ten-Minute Book Club sister project.

The above excerpt is adapted from the version known as the B-text, more of which can be read on the Harvard Chaucer Website. The eponymous Piers the Ploughman first appears in this Passus (section or, literally ‘step’) of the poem, next enlisting help from the penitents to plough his half-acre. The Ploughman figure was adopted in this period by Peasant leaders in their pressure on the feudal classes for better wages. Some of Langland’s own revisions appear to deliberately distance his poem from the violent Revolt of 1381.

To read alongside…

Langland’s contemporary Geoffrey Chaucer also creates portraits of characters defined by their class (estate), deeds and habits in the Canterbury Tales. Rather like Covetousness, ‘The Pardoner’s Tale’ gives a grim fable of 3 riotous and malignant young men undone by their jealous greed (and the tale’s teller, The Pardoner himself, is perhaps no more scrupulous: plying his false relics for high prices).

You might enjoy two other early works of literature that treat similar themes in seminal ways: the anonymous play Everyman, and Christopher Marlowe’s play Dr Faustus.

Informed that he is about to die and must prepare his moral account-book of his good deeds versus his bad deeds for when he meets God, Everyman goes to each of the seven deadly sins in turn to ask for their help in asserting his virtues and goodness. Each one turns him away or is utterly indifferent to his plight, even though they had been all too friendly throughout his life when times were good. It’s up the the very weak, undernourished Good Deeds to save the day…can she do it? Or is it too late for Everyman to beef up that side of his accounts? In Carol Ann Duffy’s powerful environmentalist adaptation of Everyman for the National Theatre in 2016, the focus was on how Everyman had treated—or mistreated—the earth through his personal greed, corruption, and ambition.

In Marlowe’s Dr Faustus, the eponymous doctor strikes a deal with the devil to go beyond the frontiers of human knowledge in exchange for his soul. Like Everyman, when the fun is over and his time is up, Faustus must justify himself before God. The punishment for his bargain with the devil is severe, as he is thrown into hell—a terrifying moment for the audience as a trap door opens and Faustus disappears into it with agonized shrieks and moans.

Are these characters all ‘live coals in the sea’?

Suggest a LitHit!

Tell us your own favourites from literature you've read, and we can feature you as a Guest Curator. Just email us with the following information:

Your full name

The title of the book you're suggesting

The location of the excerpt within the book (e.g., "in the middle of chapter 5"), or the excerpt itself copied into the email or attached to it (in Word)

Why you love it, in just a few sentences

About LitHits

Our curation is entirely human, done by our little team of Kirsten, Alex, and Daniel.

You might also enjoy...

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on our newsletter:

kshepherdb@yahoo.co.uk

Graphic design by Sara Azmy

All curation content © 2025 LitHits. All rights reserved.