A Memorable Opening...

Often emulated but rarely matched, the opening lines of Charles Dickens's 1860 novel Great Expectations masterfully set the plot in motion.

My father’s family name being Pirrip, and my Christian name Philip, my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than Pip. So, I called myself Pip, and came to be called Pip.

I give Pirrip as my father’s family name, on the authority of his tombstone and my sister,—Mrs. Joe Gargery, who married the blacksmith. As I never saw my father or my mother, and never saw any likeness of either of them (for their days were long before the days of photographs), my first fancies regarding what they were like were unreasonably derived from their tombstones. The shape of the letters on my father’s, gave me an odd idea that he was a square, stout, dark man, with curly black hair. From the character and turn of the inscription, “Also Georgiana Wife of the Above,” I drew a childish conclusion that my mother was freckled and sickly. To five little stone lozenges, each about a foot and a half long, which were arranged in a neat row beside their grave, and were sacred to the memory of five little brothers of mine,—who gave up trying to get a living, exceedingly early in that universal struggle,—I am indebted for a belief I religiously entertained that they had all been born on their backs with their hands in their trousers-pockets, and had never taken them out in this state of existence.

Ours was the marsh country, down by the river, within, as the river wound, twenty miles of the sea. My first most vivid and broad impression of the identity of things seems to me to have been gained on a memorable raw afternoon towards evening. At such a time I found out for certain that this bleak place overgrown with nettles was the churchyard; and that Philip Pirrip, late of this parish, and also Georgiana wife of the above, were dead and buried; and that Alexander, Bartholomew, Abraham, Tobias, and Roger, infant children of the aforesaid, were also dead and buried; and that the dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dikes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes; and that the low leaden line beyond was the river; and that the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing was the sea; and that the small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry, was Pip.

“Hold your noise!” cried a terrible voice, as a man started up from among the graves at the side of the church porch. “Keep still, you little devil, or I’ll cut your throat!”

A fearful man, all in coarse grey, with a great iron on his leg. A man with no hat, and with broken shoes, and with an old rag tied round his head. A man who had been soaked in water, and smothered in mud, and lamed by stones, and cut by flints, and stung by nettles, and torn by briars; who limped, and shivered, and glared, and growled; and whose teeth chattered in his head as he seized me by the chin.

“Oh! Don’t cut my throat, sir,” I pleaded in terror. “Pray don’t do it, sir.”

“Tell us your name!” said the man. “Quick!”

“Pip, sir.”

“Once more,” said the man, staring at me. “Give it mouth!”

“Pip. Pip, sir.”

“Show us where you live,” said the man. “Pint out the place!”

I pointed to where our village lay, on the flat in-shore among the alder-trees and pollards, a mile or more from the church.

The man, after looking at me for a moment, turned me upside down, and emptied my pockets. There was nothing in them but a piece of bread. When the church came to itself,—for he was so sudden and strong that he made it go head over heels before me, and I saw the steeple under my feet,—when the church came to itself, I say, I was seated on a high tombstone, trembling while he ate the bread ravenously.

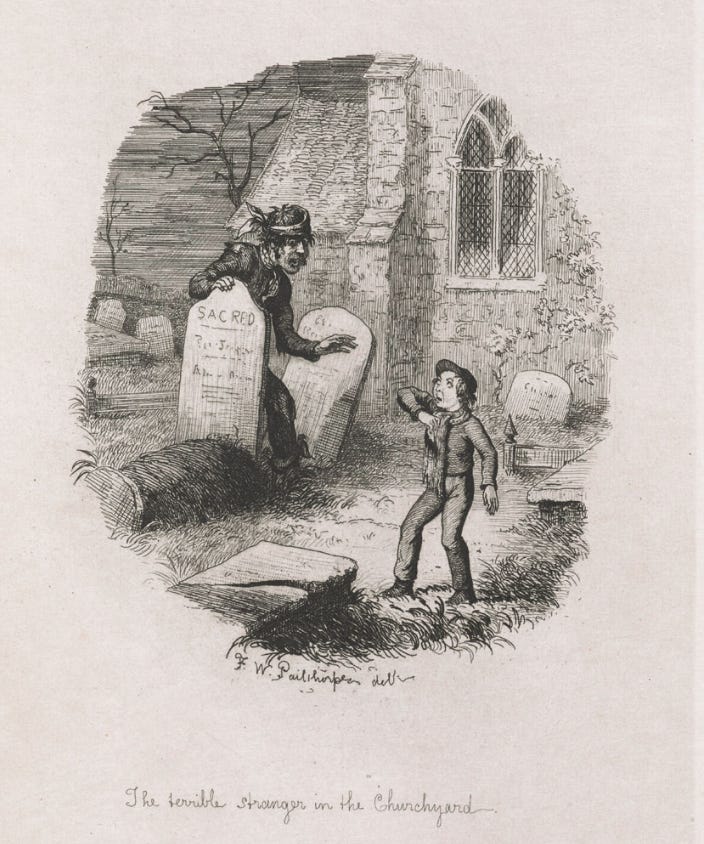

This is Frederick W Pailthorpe's illustration of the scene from an 1885 edition of the novel. For more, see the British Library website.

Why we love this passage…

Identity, memory, childhood, fear, and evocation of place — some of the key ingredients of modern literature are beautifully embroidered in these opening passages.

Ours was the marsh country, down by the river, within, as the river wound, twenty miles of the sea. My first most vivid and broad impression of the identity of things seems to me to have been gained on a memorable raw afternoon towards evening.

Yet, despite its technical sophistication, what makes this passage so evocative is its sheer thrill: an innocent young boy meets a convict in the marshes without knowing the twists and turns of what’s to come.

We also love the way Pip deciphers the letters on the gravestones, as they help him imagine the parents and brothers he cannot now remember.

About the Author

Charles Dickens (1812-70) was a tremendously prolific writer whose works include the novels Oliver Twist, Hard Times, David Copperfield, Bleak House, Our Mutual Friend, and Little Dorrit, plus dozens of short stories and volumes of journalism. Many of Dickens’s novels, including Great Expectations, unsettled the boundaries between autobiography and fiction.

To read alongside…

The influence of Great Expectations and related works such as David Copperfield on later writers is deep and lasting; but Dickens’s work has also been important for artists to critique, revise, and parody.

JD Salinger was one of several writers who would parody the Dickens’s opening in their novels. The Catcher in the Rye (1951) begins, ‘If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap…’ Also with a wry nod to the author and his vast influence on literature, Paul Beatty’s satirical, Man Booker Prize-winning novel The Sellout (2015) about race in America is set in a fictional town called Dickens, California. Staying with satire, Evelyn Waugh’s novel A Handful of Dust (1934) ends with the main character held hostage in the Brazilian rainforest and condemned to end his days reading all of Dickens’s works aloud to his captor.

Then there is the experimental writer Kathy Acker’s transgressive take on the novel, also called Great Expectations (1982), which rewrites the novel through a visceral, twentieth-century feminist lens. More recently, the British comedian Eddie Izzard has appeared in an ambitious adaptation of the novel as a two hour, one-woman show written by the artist’s brother, which debuted in New York last December.

Suggest a LitHit!

Tell us your own favourites from literature you've read, and we can feature you as a Guest Curator. Just email us with the following information:

Your full name

The title of the book you're suggesting

The location of the excerpt within the book (e.g., "in the middle of chapter 5"), or the excerpt itself copied into the email or attached to it (in Word)

Why you love it, in just a few sentences

About LitHits

Right book, right place, right time — www.lit-hits.co.uk

LitHits helps you make time for reading by bringing you unabridged excerpts from brilliant literature that you can read on the go, anytime or any place. Our curators carefully select and frame each excerpt so that you can dive right in. We are more than a book recommendation site: we connect you with a powerful, enduring piece of literature, served directly to your mobile phone, tablet or computer.

Today's guest curators...

Dr Daniel Abdalla, core member of LitHits and an expert in nineteenth and twentieth-century literature, particularly its relationship to science, and Prof Kirsten Shepherd-Barr.

You might also enjoy...

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on our newsletter:

kirsten@lit-hits.co.uk

Graphic design by Sara Azmy

All curation content © 2023 LitHits. All rights reserved.