A Multi-Dimensional Romance

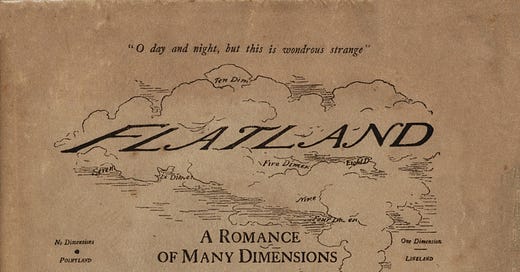

Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by A Square (Edwin Abbott Abbott)

Flatland is a satire purportedly written by a citizen--called, punningly, A Square--of the so-called Two Dimensional Flatland and addressed to us, the citizens of Three Dimensional Spaceland.

I call our world Flatland, not because we call it so, but to make its nature clearer to you, my happy readers, who are privileged to live in Space.

Imagine a vast sheet of paper on which straight Lines, Triangles, Squares, Pentagons, Hexagons, and other figures, instead of remaining fixed in their places, move freely about, on or in the surface, but without the power of rising above or sinking below it, very much like shadows—only hard with luminous edges—and you will then have a pretty correct notion of my country and countrymen. Alas, a few years ago, I should have said “my universe:” but now my mind has been opened to higher views of things.

In such a country, you will perceive at once that it is impossible that there should be anything of what you call a “solid” kind; but I dare say you will suppose that we could at least distinguish by sight the Triangles, Squares, and other figures, moving about as I have described them. On the contrary, we could see nothing of the kind, not at least so as to distinguish one figure from another. Nothing was visible, nor could be visible, to us, except Straight Lines; and the necessity of this I will speedily demonstrate.

Place a penny on the middle of one of your tables in Space; and leaning over it, look down upon it. It will appear a circle.

But now, drawing back to the edge of the table, gradually lower your eye (thus bringing yourself more and more into the condition of the inhabitants of Flatland), and you will find the penny becoming more and more oval to your view, and at last when you have placed your eye exactly on the edge of the table (so that you are, as it were, actually a Flatlander) the penny will then have ceased to appear oval at all, and will have become, so far as you can see, a straight line.

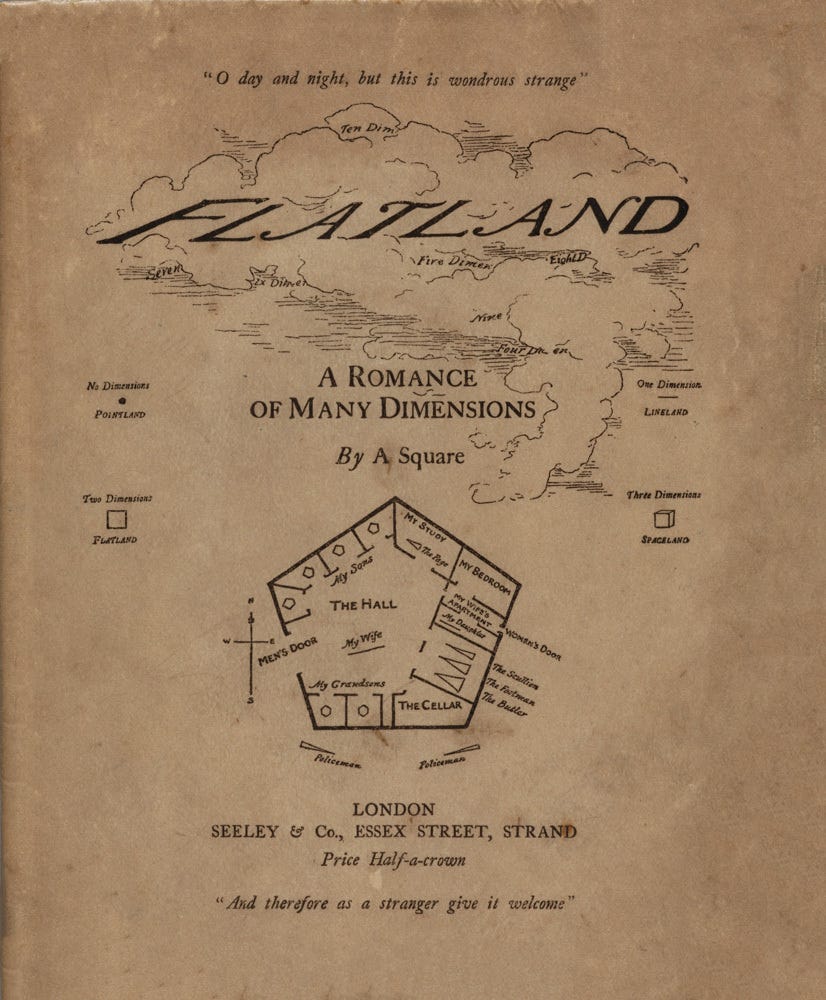

The same thing would happen if you were to treat in the same way a Triangle, or a Square, or any other figure cut out from pasteboard. As soon as you look at it with your eye on the edge of the table, you will find that it ceases to appear to you as a figure, and that it becomes in appearance a straight line. Take for example an equilateral Triangle—who represents with us a Tradesman of the respectable class. Figure 1 represents the Tradesman as you would see him while you were bending over him from above; figures 2 and 3 represent the Tradesman, as you would see him if your eye were close to the level, or all but on the level of the table; and if your eye were quite on the level of the table (and that is how we see him in Flatland) you would see nothing but a straight line.

When I was in Spaceland I heard that your sailors have very similar experiences while they traverse your seas and discern some distant island or coast lying on the horizon. The far-off land may have bays, forelands, angles in and out to any number and extent; yet at a distance you see none of these (unless indeed your sun shines bright upon them revealing the projections and retirements by means of light and shade), nothing but a grey unbroken line upon the water.

About the author

Edwin Abbott Abbott (1838-1926) is best known for Flatland, but had various careers and interests as a schoolmaster, theologian, and Anglican priest.

What We Love About This Passage...

At first glance, the premise of Flatland might strike us as somewhat whimsical, making the novel seem like a dusty Victorian relic related to the gramophone, or early science fiction and utopian texts such as Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) and Samuel Butler's Erewhon (1872).

But Abbott's light-hearted opening lines suggest a deeper concern: How do you describe something from a perspective that might not even be possible? In this daring experiment to write about the universe as we know it from a different spatial dimension, Abbott shows an incredible ability to imagine the world in a radically different way.

This interest is related to the enormous advances in nineteenth-century science and anthropology, such as Charles Darwin's new theories of evolution encapsulated in On The Origin of the Species (1859) and Sir George James Frazer's The Golden Bough (1890). But to a large extent, Abbott's interest in the problem came from a different influence, his theological career. Flatland is an attempt to imagine how humans might understand their relationship to a higher, spiritual dimension.

To Read Alongside...

Nineteenth-century mathematicians are also the subject of Sydney Padua's graphic novel, The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage: The (Mostly) True Story of the First Computer (2015). It re-imagines the fascinating life of Ada Lovelace, whose work on algorithms represents the beginnings of modern computer science. As eager readers of literature and seekers of connections between science and the humanities, we can't help but add that she was Lord Byron's daughter!

Abbott's varied life reminds us of his contemporary Lewis Carroll, or Charles Lutwidge Dodson, the author of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), whose interest in puzzles and logical conundrums stemmed from his interests in mathematics. This is explored memorably in Robert Douglas-Fairhurst's biographical account The Story of Alice: Lewis Carroll and the Secret History of Wonderland (2015).

A century later, science fiction writers such as Octavia Butler and Kurt Vonnegut also tried to imagine viewing the universe from different perspectives. In Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five (1969), the alien race of Tralfamadorians can see all of the fourth dimension, time. Experiencing life in this way has given them a distinctly fatalist view, which is summarized in their catchphrase: "So it goes."

Suggest a LitHit!

Tell us your own favourites from literature you've read, and we can feature you as a Guest Curator. Just email us with the following information:

Your full name

The title of the book you're suggesting

The location of the excerpt within the book (e.g., "in the middle of chapter 5"), or the excerpt itself copied into the email or attached to it (in Word)

Why you love it, in just a few sentences

About LitHits

Right book, right place, right time — www.lit-hits.co.uk

LitHits helps you make time for reading by bringing you unabridged excerpts from brilliant literature that you can read on the go, anytime or any place. Our curators carefully select and frame each excerpt so that you can dive right in. We are more than a book recommendation site: we connect you with a powerful, enduring piece of literature, served directly to your mobile phone, tablet or computer.

Today's guest curator...

Dr Daniel Abdalla, core member of LitHits and an expert in nineteenth and twentieth-century literature, particularly its relationship to science.

You might also enjoy...

“Five Tips to Get Reading Again if You’ve Struggled During the Pandemic,” The Conversation (8 January 2021): https://theconversation.com/five-tips-to-get-reading-again-if-youve-struggled-during-the-pandemic-152904

Writers Make Worlds: https://writersmakeworlds.com/

The Ten Minute Book Club: https://www.english.ox.ac.uk/ten-minute-book-club

Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/

Standard Ebooks: https://standardebooks.org/

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on our newsletter:

kirsten@lit-hits.co.uk

Graphic design by Sara Azmy

All curation content © 2022 LitHits. All rights reserved.