Looking Out in New York

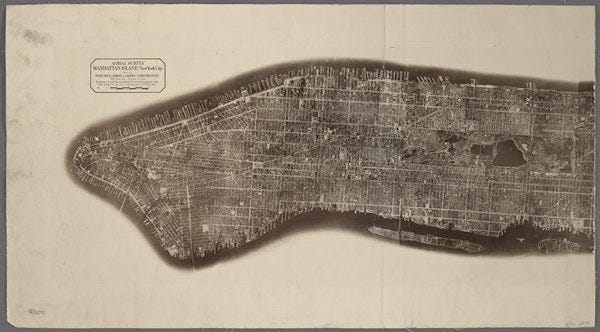

Edith Wharton's first published short story features a mysterious figure who prizes her view of the city...

From ‘Mrs. Manstey’s View’ (1891) by Edith Wharton

The view from Mrs. Manstey’s window was not a striking one, but to her at least it was full of interest and beauty. Mrs. Manstey occupied the back room on the third floor of a New York boarding-house, in a street where the ash-barrels lingered late on the sidewalk and the gaps in the pavement would have staggered a Quintus Curtius. She was the widow of a clerk in a large wholesale house, and his death had left her alone, for her only daughter had married in California, and could not afford the long journey to New York to see her mother. Mrs. Manstey, perhaps, might have joined her daughter in the West, but they had now been so many years apart that they had ceased to feel any need of each other’s society, and their intercourse had long been limited to the exchange of a few perfunctory letters, written with indifference by the daughter, and with difficulty by Mrs. Manstey, whose right hand was growing stiff with gout. Even had she felt a stronger desire for her daughter’s companionship, Mrs. Manstey’s increasing infirmity, which caused her to dread the three flights of stairs between her room and the street, would have given her pause on the eve of undertaking so long a journey; and without perhaps formulating these reasons she had long since accepted as a matter of course her solitary life in New York.

She was, indeed, not quite lonely, for a few friends still toiled up now and then to her room; but their visits grew rare as the years went by. Mrs. Manstey had never been a sociable woman, and during her husband’s lifetime his companionship had been all-sufficient to her. For many years she had cherished a desire to live in the country, to have a hen-house and a garden; but this longing had faded with age, leaving only in the breast of the uncommunicative old woman a vague tenderness for plants and animals. It was, perhaps, this tenderness which made her cling so fervently to her view from her window, a view in which the most optimistic eye would at first have failed to discover anything admirable.

What we love about this excerpt….

Wharton’s prose manages to communicate profound depths of feeling and the duration of a life through sparing imagery. Mrs. Manstey’s slowly changing life seems, at least from the look of things, to be a sad one, especially given the lack of nice things to look at (gaps in the pavement that would have even bothered an Ancient Roman). But her close knowledge of the detail outside her window and daily observations of it become a true source of pleasure, and a key to enduring her isolated life. The view out of Mrs Manstey’s window may not be all that extraordinary or exciting, in fact it might be drab to any other viewer, but it is hers.

Wharton’s friend, the novelist Henry James, once strongly encouraged his readers to be keenly attuned to the world: ‘Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost.’ Mrs. Manstey is perhaps one of those people.

About the author

Edith Wharton (1862-1937) was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, which she was awarded for The Age of Innocence (1920). Although born in the United States, she spent much of her life living in France. During the First World War, her commitment to the war efforts of her adopted country earned her the Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, the country's highest award. Her other best-known works, such as The House of Mirth (1905), Ethan Frome (1911), and The Custom of the Country (1913), show her characteristic wit and ability to unmask the hypocritical fashions of the day—and do so devastatingly.

To read alongside...

We have featured another short story by Wharton in a past newsletter.

You might also enjoy our newsletter featuring another remarkable view—this time it’s Charles Darwin’s attentive contemplation of a riverbank and its multifarious life forms.

An entangled bank

It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have …

Suggest a LitHit!

Tell us your own favourites from literature you've read, and become a Guest Curator. Just email us with the following information:

Your full name (and whether you want to be named or be anonymous in the newsletter—either option is fine!)

The title of the book you're suggesting

The location of the excerpt within the book (e.g., "in the middle of chapter 5"), or the excerpt itself copied into the email or attached to it (in Word)

Why you love it, in just a few sentences

**Please note that we welcome all suggestions but at the moment we can only release excerpts that are out of copyright and in the public domain. This means 75 years or more since the author's death. You can find many such out-of-copyright texts on the internet, for example at Project Gutenberg and Standard Ebooks.

About LitHits

You might also enjoy...

Writers Make Worlds: https://writersmakeworlds.com/

The Ten Minute Book Club: https://www.english.ox.ac.uk/ten-minute-book-club

Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/

Standard Ebooks: https://standardebooks.org/

The Poetry Foundation: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/

“Five Tips to Get Reading Again if You’ve Struggled During the Pandemic,” The Conversation (8 January 2021): https://theconversation.com/five-tips-to-get-reading-again-if-youve-struggled-during-the-pandemic-152904

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on our newsletter:

kshepherdb@yahoo.co.uk

Graphic design by Sara Azmy

All curation content © 2025 LitHits. All rights reserved.