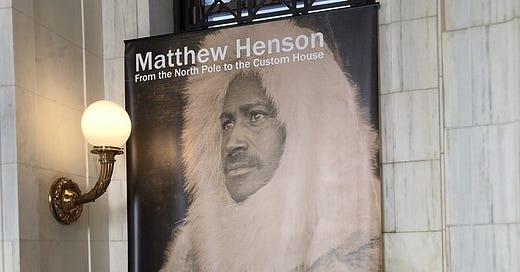

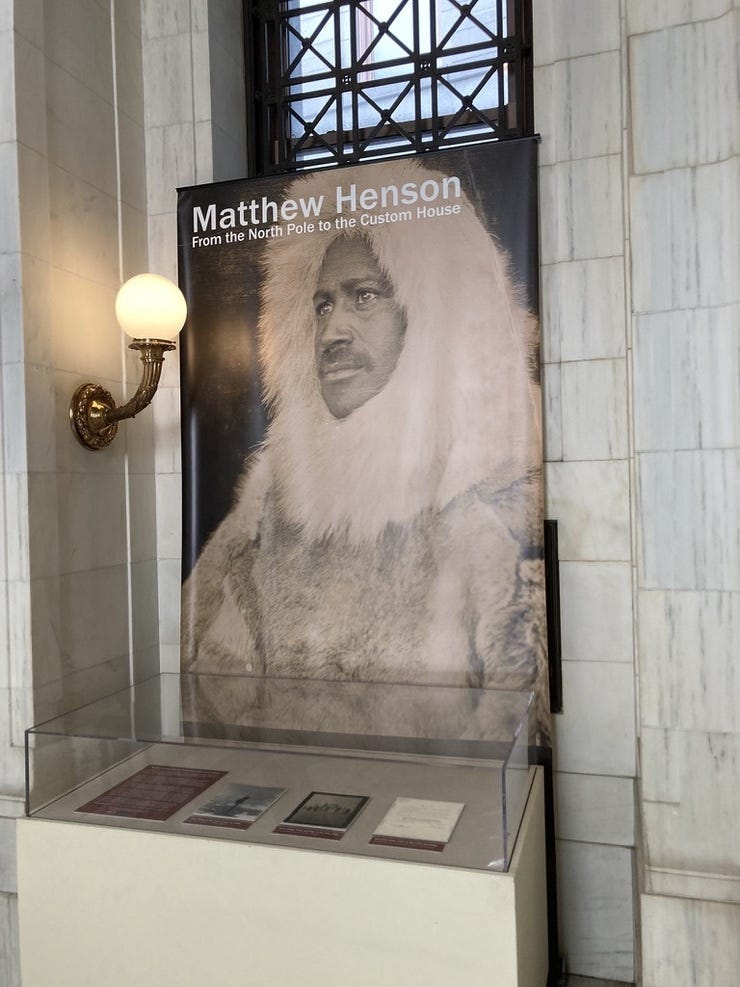

Matthew Henson, once-forgotten Polar explorer

Matthew A Henson was a key member of the famed expedition–led by Commander Robert E Peary–that claimed to be the first to reach the geographic North Pole in 1909. In his memoir, Henson details the intensity of the climate, his relationship to the Polar Inuit peoples on whose assistance he depended, and the scale of expedition's achievements. We celebrate Henson's achievements as we welcome Black History Month here in the UK.

Walking wide, like the polar bear, we crept after, and without further incident reached the opposite side of the lead. My team had reached there before me and, with human intelligence, the dogs had dragged the sledge to a place of safety and were sitting on their haunches, with ears cocked forward, watching us in our precarious predicament. They seemed to rejoice at our deliverance, and as I went among them and untangled their traces I could not forbear giving each one an affectionate pat on the head.

For the next five hours our trail lay over heavy pressure ridges, in some places sixty feet high. We had to make a trail over the mountains of ice and then come back for the sledges. A difficult climb began. Pushing from our very toes, straining every muscle, urging the dogs with voice and whip, we guided the sledges. On several occasions the dogs gave it up, standing still in their tracks, and we had to hold the sledges with the strength of our bones and muscles to prevent them from sliding backwards. When we had regained our equilibrium the dogs were again started, and in this way we gained the tops of the pressure-ridges.

Going down on the opposite side was more nerve-racking. On the descent of one ridge, in spite of the experienced care of Ootah, the sledge bounded away from him, and at a declivity of thirty feet was completely wrecked. The frightened dogs dashed wildly in every direction to escape the falling sledge, and as quickly as possible we slid down the steep incline, at the same time guiding the dogs attached to the two remaining sledges. We rushed over, my two boys and I, to the spot where the poor dogs stood trembling with fright. We released them from the tangle they were in, and, with kind words and pats of the hand on their heads, quieted them. For over an hour we struggled with the broken pieces of the wreck and finally lashed them together with strips of oog-sook (seal-hide). We said nothing to the Commander when he caught up with us, but his quick eye took in at a glance the experience we had been through. The repairs having been completed, we again started. Before us stretched a heavy, old floe, giving us good going until we reached the lead, when the order was given to camp. We built our igloos, and boiled the tea and had what we called supper.

What we love about this passage...

Henson's writing packs the drama of the arduous trek into each detail, and his language almost absorbs its surroundings–such as when he describes his team's movement like a "polar bear" or uses the Inuit word oog-sook for seal-hide. Henson showed a sustained interest in language throughout his career, and the linguist Kenn Harper notes that Henson "was the only one of all those who ever accompanied Peary north who learned to speak the language of the Inuit in anything but a halting fashion."

Much of the immediacy of Henson's memoir emerges from the fact that he wrote it on the trail, and sections of the book feature almost comical episodes of a person trying to keep up with a diary in extreme circumstances. These details make the book a fascinating historical and literary document, yet, until recently, Henson's contributions to Polar exploration have been entirely forgotten–despite the fact that he may have been the first member of his party to reach the North Pole.

As the introductions to Henson's memoir by Booker T Washington and Peary remind us, as an African-American explorer at the turn of the century, Henson's achievements helped to change many of the troubling conceptions of race and nation of the time. And yet, there are other members of the team whose stories have not been told, such as the man referred to as Ootah, a member of the team from the indigenous Polar Inuit group.

About the author

Matthew A Henson (1866-1955) regularly visited the Arctic with Commander Robert E Peary from 1891. In 1937, he was the first African American to be made a life member of The Explorers Club (they awarded Peary a medal in 1914). Despite Henson's fame in the years following the successful expedition to the North Pole, he spent much of the following decades living in obscurity.

To read alongside...

Henson writes that one of the few opportunities for leisure on the expedition was reading: "During the long dreary midnights of the Arctic winter, I spent many a pleasant hour with my books." These included popular turn-of-the-century reads: Charles Dickens's Bleak House, Rudyard Kipling's Barrack Room Ballads and the poems of Thomas Hood.

The contemporary playwright Mojisola Adebayo has dramatized Henson's journey in the play Matt Henson: North Star and also written a one-woman performance Moj of the Antarctic: An African Odyssey (2006), a re-telling of Ellen Craft’s escape from slavery that imagines her journey taking her as far as Antarctica. (See LitHits Newsletter 21, 'The Amazing, Cross-Dressing Escape of Ellen Craft,' for a taste of her dramatic life.)

In the same period as Henson's Arctic exploration, the Klondike stories of Jack London emerged as American classics, particularly The Call of the Wild and White Fang. More recently, scholars have been critical of the conventional American and European viewpoints of the region and have tried to tell the stories of the people who have long called the Arctic home. One example of this is Kenn Harper's Minik: The New York Eskimo, which relates the troubling story of six Polar Inuit who were commercially exhibited in New York in 1897.

Suggest a LitHit!

Tell us your own favourites from literature you've read, and we can feature you as a Guest Curator. Just email us with the following information:

Your full name

The title of the book you're suggesting

The location of the excerpt within the book (e.g., "in the middle of chapter 5"), or the excerpt itself copied into the email or attached to it (in Word)

Why you love it, in just a few sentences

**Please note that we welcome all suggestions but at the moment we can only release excerpts that are out of copyright and in the public domain. This means 75 years or more since the author's death. You can find many such out-of-copyright texts on the internet, for example at Project Gutenberg and Standard Ebooks.

About LitHits

Today's guest curator...

Dr Daniel Abdalla, core member of LitHits and an expert in nineteenth and twentieth-century literature, is currently working on a project related to the Arctic regions.

You might also enjoy...

“Five Tips to Get Reading Again if You’ve Struggled During the Pandemic,” The Conversation (8 January 2021): https://theconversation.com/five-tips-to-get-reading-again-if-youve-struggled-during-the-pandemic-152904

Writers Make Worlds: https://writersmakeworlds.com/

The Ten Minute Book Club: https://www.english.ox.ac.uk/ten-minute-book-club

Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/

Standard Ebooks: https://standardebooks.org/

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on our newsletter:

kirsten@lit-hits.co.uk

Graphic design by Sara Azmy

All curation content © 2022 LitHits. All rights reserved.