No, no, go not to Lethe, neither twist

Wolf's-bane, tight-rooted, for its poisonous wine;

Nor suffer thy pale forehead to be kiss'd

By nightshade, ruby grape of Proserpine;

Make not your rosary of yew-berries,

Nor let the beetle, nor the death-moth be

Your mournful Psyche, nor the downy owl

A partner in your sorrow's mysteries;

For shade to shade will come too drowsily,

And drown the wakeful anguish of the soul.

But when the melancholy fit shall fall

Sudden from heaven like a weeping cloud,

That fosters the droop-headed flowers all,

And hides the green hill in an April shroud;

Then glut thy sorrow on a morning rose,

Or on the rainbow of the salt sand-wave,

Or on the wealth of globed peonies;

Or if thy mistress some rich anger shows,

Emprison her soft hand, and let her rave,

And feed deep, deep upon her peerless eyes.

She dwells with Beauty—Beauty that must die;

And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips

Bidding adieu; and aching Pleasure nigh,

Turning to poison while the bee-mouth sips:

Ay, in the very temple of Delight

Veil'd Melancholy has her sovran shrine,

Though seen of none save him whose strenuous tongue

Can burst Joy's grape against his palate fine;

His soul shalt taste the sadness of her might,

And be among her cloudy trophies hung.About the Author

John Keats (1795-1821) was a Romantic poet of the same generation as Shelley and Byron. Both of his parents died while he was still young. At the age of 15 he left school to be apprenticed to a surgeon for five years, then enrolled to study medicine at Guy’s Hospital in London. He also continued to develop his poetic talents and, with the encouragement of friends, particularly Leigh Hunt, he began to publish his poems in 1817. He achieved extraordinary success even within his brief lifetime, cut short by tuberculosis at the age of 25. More about his life and work can be found here.

What we love about this poem…

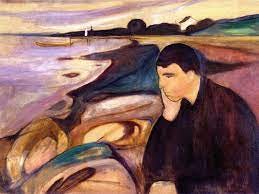

You might expect a poem about melancholy to be lethargic and dull, but this is a surprisingly energetic and varied work that squeezes a lot of ideas into its three short stanzas. Part of the energy comes from the sheer variety and force of the language, so rich in nature imagery and classical references; part of it comes from the lively sense of direction and transformation, moving from a tone of warning and resistance (the first stanza almost entirely in negative commands, that we must guard against the onset of melancholy) to an abrupt injunction to do the opposite: if melancholy does overtake us, just give in to it wholeheartedly. Finally, the third stanza reveals the truth Keats wants to drive home: that it’s never an ‘either-or’ situation, where we’re sad one moment and happy another; melancholy always exists alongside joy, and in this mingling can be found both beauty and truth, the pillars of the Romantic vision.

Suggest a LitHit!

Tell us your own favourites from literature you've read, and we can feature you as a Guest Curator. Just email us with the following information:

Your full name

The title of the book you're suggesting

The location of the excerpt within the book (e.g., "in the middle of chapter 5"), or the excerpt itself copied into the email or attached to it (in Word)

Why you love it, in just a few sentences

About LitHits

LitHits helps you make time for reading by bringing you unabridged excerpts from brilliant literature that you can read on the go, anytime or any place. Our curators carefully select and frame each excerpt so that you can dive right in. We are more than a book recommendation site: we connect you with a powerful, enduring piece of literature, served directly to your mobile phone, tablet or computer.

You might also enjoy...

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on our newsletter:

kshepherdb@yahoo.co.uk

Graphic design by Sara Azmy

All curation content © 2024 LitHits. All rights reserved.