Emily Dickinson, ‘Dear March — Come in —’

Dear March — Come in —

How glad I am —

I hoped for you before —

Put down your Hat —

You must have walked —

How out of Breath you are —

Dear March, Come right up the stairs with me —

I have so much to tell —

I got your Letter, and the Birds —

The Maples never knew that you were coming — till I called

I declare — how Red their Faces grew —

But March, forgive me — and

All those Hills you left for me to Hue —

There was no Purple suitable —

You took it all with you —

Who knocks? That April.

Lock the Door —

I will not be pursued —

He stayed away a Year to call

When I am occupied —

But trifles look so trivial

As soon as you have come

That Blame is just as dear as Praise

And Praise as mere as Blame —

What we love about this poem…

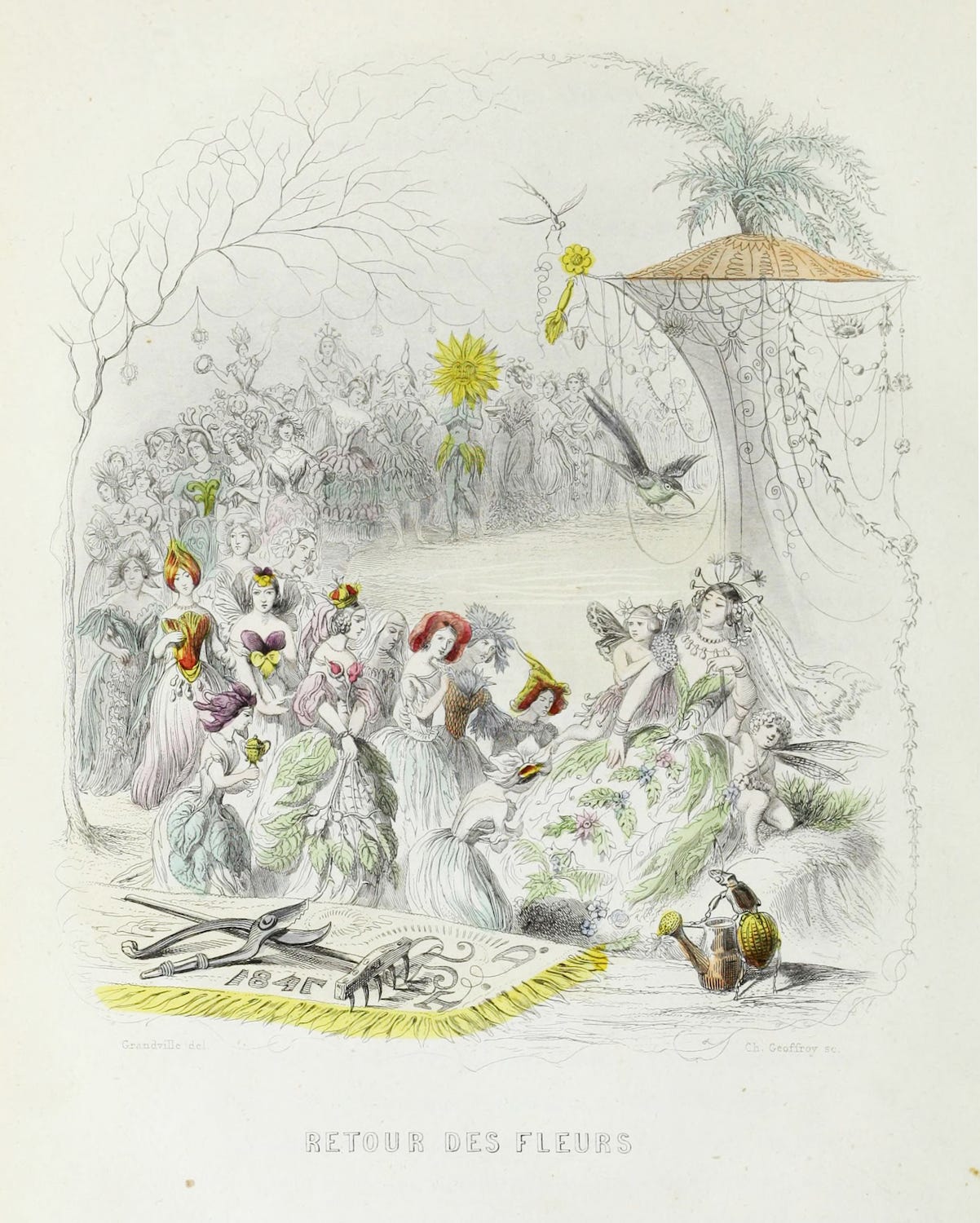

March: an out of breath person wearing a hat, who knocks and is invited upstairs. Once upstairs, March and the poem’s speaker are disturbed by another knock from April, who is something of an annoyance. The strangeness of the episode is quintessential Dickinson, as are the touches of humor and personification—maples trees turning red with embarrassment—and the depth of feeling in the final part: who can bother with trifles when the sunshine of March has returned?

About the Author

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) is widely regarded as one of the most important and innovative American poets. She spent most of her life in Amherst, Massachusetts, living reclusively but writing constantly, both poetry and letters. Her work was published after her death and became an instant success. She once described the power of poetry as something that ‘takes the top of your head off’.

To read alongside…

In literary terms, Dickinson’s poem technically uses apostrophe, an address to a personified and absent entity—in this case, ‘March’ and ‘April.’ This device links it to John Keats’s poem ‘To Autumn’ which directly addresses its title season, but rather formally, at least compared to Dickinson’s harried March. Perhaps Dickinson saw her own poem as a response to Keats’s line, ‘Where are the songs of spring?’

We have written before about Geoffrey Chaucer’s similar device in the opening of The Canterbury Tales ‘General Prologue’:

Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote / The droghte of March hath perced to the roote (‘When that April with his sweet showers has pierced the drought of March to the root’). It is not quite apostrophe but similarly makes personages of April and March, and identifies an elemental conflict between those two months (though April is far more welcome to Chaucer than to Dickinson!)

We have featured other Emily Dickinson poems which make use of apostrophe, such as ‘“Hope” is the thing with feathers’"

'"Hope" is the thing with feathers'

‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers -That perches in the soul -And sings the tune without the words -And never stops - at all - And sweetest - in the Gale - is heard -And sore must be the storm -That could abash the little BirdThat kept so many warm -

And finally, Dickinson’s personification of March brings to mind the ‘March Hare’ in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), whose erratic and highly-strung behaviour at the tea party cleverly draws on the phrase ‘mad as a March hare’, an English saying about the mating habits of hares in springtime.

Suggest a LitHit!

Tell us your own favourites from literature you've read, and we can feature you as a Guest Curator. Just email us with the following information:

Your full name

The title of the book you're suggesting

The location of the excerpt within the book (e.g., "in the middle of chapter 5"), or the excerpt itself copied into the email or attached to it (in Word)

Why you love it, in just a few sentences

About LitHits

Our curation is entirely human, done by our little team of Kirsten, Alex, and Daniel.

You might also enjoy...

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on our newsletter:

kshepherdb@yahoo.co.uk

Graphic design by Sara Azmy

All curation content © 2025 LitHits. All rights reserved.