State of the Nation

As seamstress and confidante to President Lincoln's wife, former slave Elizabeth Keckley bore witness to intimate moments in the White House such as this--and used them to reflect on racism

Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes; or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House

"Where's my book, Ma? Get my book quick. I will say my lesson," and he jumped about the room, boisterously, boy-like.

"Be quiet, Tad. Here is your book, and we will now begin the first lesson," said his mother, as she seated herself in an easy-chair.

Tad had always been much humored by his parents, especially by his father. He suffered from a slight impediment in his speech, and had never been made to go to school; consequently his book knowledge was very limited. I knew that his education had been neglected, but had no idea he was so deficient as the first lesson at Hyde Park proved him to be.

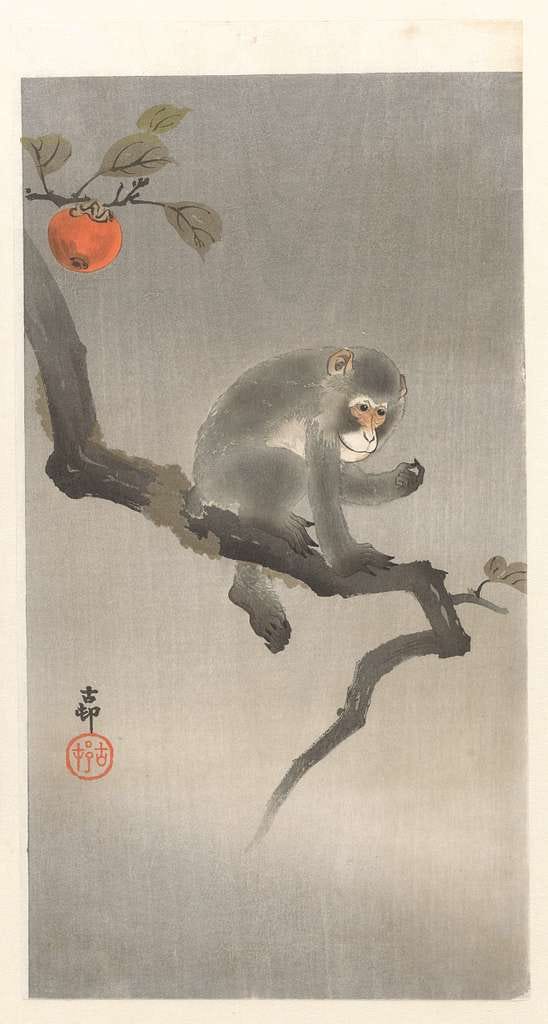

Drawing a low chair to his mother's side, he opened his book, and began to slowly spell the first word, "A-P-E."

"Well, what does A-p-e spell?"

"Monkey," was the instant rejoinder. The word was illustrated by a small wood-cut of an ape, which looked to Tad's eyes very much like a monkey; and his pronunciation was guided by the picture, and not by the sounds of the different letters.

"Nonsense!" exclaimed his mother. "A-p-e does not spell monkey."

"Does spell monkey! Isn't that a monkey?" and Tad pointed triumphantly to the picture.

"No, it is not a monkey."

"Not a monkey! what is it, then?"

"An ape."

"An ape! 'taint an ape. Don't I know a monkey when I see it?"

"No, if you say that is a monkey."

"I do know a monkey. I've seen lots of them in the street with the organs. I know a monkey better than you do, 'cause I always go out into the street to see them when they come by, and you don't."

"But, Tad, listen to me. An ape is a species of the monkey. It looks like a monkey, but it is not a monkey."

"It shouldn't look like a monkey, then. Here, Yib"—he always called me Yib—"isn't this a monkey, and don't A-p-e spell monkey? Ma don't know anything about it;" and he thrust his book into my face in an earnest, excited manner.

I could not longer restrain myself, and burst out laughing. Tad looked very much offended, and I hastened to say: "I beg your pardon, Master Tad; I hope that you will excuse my want of politeness."

He bowed his head in a patronizing way, and returned to the original question: "Isn't this a monkey? Don't A-p-e spell monkey?"

"No, Tad; your mother is right. A-p-e spells ape."

"You don't know as much as Ma. Both of you don't know anything;" and Master Tad's eyes flashed with indignation.

Robert entered the room, and the question was referred to him. After many explanations, he succeeded in convincing Tad that A-p-e does not spell monkey, and the balance of the lesson was got over with less difficulty.

Whenever I think of this incident I am tempted to laugh; and then it occurs to me that had Tad been a negro boy, not the son of a President, and so difficult to instruct, he would have been called thick-skulled, and would have been held up as an example of the inferiority of race. I know many full negro boys, able to read and write, who are not older than Tad Lincoln was when he persisted that A-p-e spelt monkey. Do not imagine that I desire to reflect upon the intellect of little Tad. Not at all; he is a bright boy, a son that will do honor to the genius and greatness of his father; I only mean to say that some incidents are about as damaging to one side of the question as to the other. If a colored boy appears dull, so does a white boy sometimes; and if a whole race is judged by a single example of apparent dulness, another race should be judged by a similar example.

About the Author

Elizabeth Keckley (1818-1907) was born into slavery in Virginia. A skilled seamstress, she bought her and her son’s freedom in 1855 and managed to get to Washington, D.C. and set up her own business as a modiste, a term she pointedly called herself to draw attention to the artistry and skill that dressmaking involved. She quickly gained the attention of the First Lady, Mary Todd Lincoln, who hired her as her personal seamstress to live with the Lincolns in the White House.

Keckley used her position to help the many formerly enslaved people coming to Washington by establishing the Ladies’ Freedmen and Soldiers Relief Association and setting up ‘contrabands camps’ where they could receive temporary housing and support. She also introduced President Lincoln to Sojourner Truth, the Abolitionist whose famous 1851 speech ‘Ain’t I a Woman’ had highlighted the lack of awareness of the struggles of Black women in the United States.

You can read more of Keckley’s memoir here.

What we love about this passage…

The anecdote about Tad’s honest mistake has a tenderness to it, as Keckley suggests that Tad struggles with speech and has to be home-schooled. But she concludes with quiet rage at the double standard by which Black and white children are judged.

What shocked many readers about Keckley’s sensational book was that a Black ex-slave woman dared to narrate white lives, let alone the most famous in the country; that she should have had such privileged access to them; and that she was an eye-witness to (and unerring judge of) their behaviour.

Equally galling to white readers was the fact that she possessed such power in Washington, albeit a very different kind from political power. Keckley’s dressmaking skill was sought after by the most famous families in the capital—an entire network of influential politicians’ wives and sometimes their husbands was dependent on her.

To Read Alongside…

Mary Prince’s The History of Mary Prince is an account by a freed slave of her experience in the Caribbean, and was the first book in England to tell the story of a Black woman’s life. Like Keckley after her, Prince fights hard for the right simply to work for her own living. You can read an excerpt from her landmark book here.

You might also enjoy The Wonderful Adventures of Mary Seacole, in which the indomitable, widely travelled nurse and cook Mary Seacole tells of a life full of energy, unflinching courage, and sheer delight in her work. You can read our past newsletter on the book here.

And finally…people who follow the Met Gala will have seen a dress inspired by one Keckley made for Mary Todd Lincoln worn by Sarah Jessica Parker last year.

Suggest a LitHit!

Tell us your own favourites from literature you've read, and we can feature you as a Guest Curator if you like. Just email us with the following information:

Your full name

The title of the book you're suggesting

The location of the excerpt within the book (e.g., "in the middle of chapter 5"), or the excerpt itself copied into the email or attached to it (in Word)

Why you love it, in just a few sentences

About LitHits

LitHits helps you make time for reading by bringing you unabridged excerpts from brilliant literature that you can read on the go, anytime or any place. Our curators carefully select and frame each excerpt so that you can dive right in. We are more than a book recommendation site: we connect you with a powerful, enduring piece of literature, served directly to your mobile phone, tablet or computer.

You might also enjoy...

A Note on Last Week’s Newsletter…

Professor Derek Attridge wrote to us about our reading of John Masefield’s ‘Sea-Fever,’ and we are delighted that he’s allowed us to share his expertise here: ‘the poem's metre is not based on a pattern of seven feet/fourteen syllables; it's a wonderful example of the swing and memorability of four-beat dolnik verse in the traditional ballad arrangement of 4 beats + 3 beats and a rest. That's why the number of syllables per line varies from 14 to 17, while the jaunty rhythm remains constant -- and is actually enhanced by the variation.’

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on our newsletter:

kshepherdb@yahoo.co.uk

Graphic design by Sara Azmy

All curation content © 2023 LitHits. All rights reserved.