Strike!

In this excerpt from Elizabeth Gaskell's novel, the labourers of Mr. Thornton's mill have begun to strike. Margaret Hale, in sympathy with them, begs Thornton to acknowledge their plight.

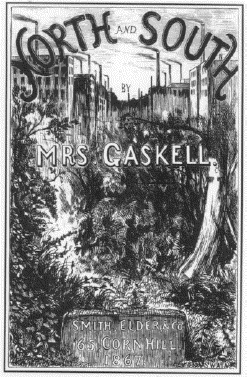

From North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell

“Keep up your courage for five minutes, Miss Hale.”

“Don’t be afraid for me,” she said hastily. “But what in five minutes? Can you do nothing to soothe these poor creatures? It is awful to see them.”

“The soldiers will be here directly, and that will bring them to reason.”

“To reason!” said Margaret, quickly. “What kind of reason?”

“The only reason that does with men that make themselves into wild beasts. By heaven! they’ve turned to the mill-door!”

“Mr. Thornton,” said Margaret, shaking all over with her passion, “go down this instant, if you are not a coward. Go down and face them like a man. Save these poor strangers, whom you have decoyed here. Speak to your workmen as if they were human beings. Speak to them kindly. Don’t let the soldiers come in and cut down poor creatures who are driven mad. I see one there who is. If you have any courage or noble quality in you, go out and speak to them, man to man!”

He turned and looked at her while she spoke. A dark cloud came over his face while he listened. He set his teeth as he heard her words.

“I will go. Perhaps I may ask you to accompany me downstairs, and bar the door behind me; my mother and sister will need that protection.”

“Oh! Mr. Thornton! I do not know—I may be wrong—only—”

But he was gone; he was downstairs in the hall; he had unbarred the front door; all she could do was to follow him quickly, and fasten it behind him, and clamber up the stairs again with a sick heart and a dizzy head. Again she took her place by the farthest window. He was on the steps below; she saw that by the direction of a thousand angry eyes; but she could neither see nor hear anything save the savage satisfaction of the rolling angry murmur. She threw the window wide open. Many in the crowd were mere boys; cruel and thoughtless,—cruel because they were thoughtless; some were men, gaunt as wolves, and mad for prey. She knew how it was; they were like Boucher,—with starving children at home—relying on ultimate success in their efforts to get higher wages, and enraged beyond measure at discovering that Irishmen were to be brought in to rob their little ones of bread. Margaret knew it all; she read it in Boucher’s face, forlornly desperate and livid with rage. If Mr. Thornton would but say something to them—let them hear his voice only—it seemed as if it would be better than this wild beating and raging against the stony silence that vouchsafed them no word, even of anger or reproach. But perhaps he was speaking now; there was a momentary hush of their noise, inarticulate as that of a troop of animals. She tore her bonnet off, and bent forward to hear. She could only see; for if Mr. Thornton had indeed made the attempt to speak, the momentary instinct to listen to him was past and gone, and the people were raging worse than ever. He stood with his arms folded; still as a statue; his face pale with repressed excitement. They were trying to intimidate him—to make him flinch; each was urging the other on to some immediate act of personal violence. Margaret felt intuitively that in an instant all would be uproar; the first touch would cause an explosion, in which, among such hundreds of infuriated men and reckless boys, even Mr. Thornton’s life would be unsafe,—that in another instant the stormy passions would have passed their bounds, and swept away all barriers of reason, or apprehension of consequence. Even while she looked, she saw lads in the background stooping to take off their heavy wooden clogs—the readiest missile they could find; she saw it was the spark to the gunpowder, and, with a cry, which no one heard, she rushed out of the room, down stairs,—she had lifted the great iron bar of the door with an imperious force—had thrown the door open wide—and was there, in face of that angry sea of men, her eyes smiting them with flaming arrows of reproach. The clogs were arrested in the hands that held them—the countenances, so fell not a moment before, now looked irresolute, and as if asking what this meant. For she stood between them and their enemy. She could not speak, but held out her arms towards them till she could recover breath.

“Oh, do not use violence! He is one man, and you are many;” but her words died away, for there was no tone in her voice; it was but a hoarse whisper. Mr. Thornton stood a little on one side; he had moved away from behind her, as if jealous of anything that should come between him and danger.

“Go!” said she, once more (and now her voice was like a cry). “The soldiers are sent for—are coming. Go peaceably. Go away. You shall have relief from your complaints, whatever they are.”

“Shall them Irish blackguards be packed back again?” asked one from out the crowd, with fierce threatening in his voice.

“Never, for your bidding!” exclaimed Mr. Thornton. And instantly the storm broke. The hootings rose and filled the air,—but Margaret did not hear them. Her eye was on the group of lads who had armed themselves with their clogs some time before. She saw their gesture—she knew its meaning—she read their aim. Another moment, and Mr. Thornton might be smitten down,—he whom she had urged and goaded to come to this perilous place. She only thought how she could save him. She threw her arms around him; she made her body into a shield from the fierce people beyond. Still, with his arms folded, he shook her off.

“Go away,” said he, in his deep voice. “This is no place for you.”

“It is,” said she. “You did not see what I saw.” If she thought her sex would be a protection,—if, with shrinking eyes she had turned away from the terrible anger of these men, in any hope that ere she looked again they would have paused and reflected, and slunk away, and vanished,—she was wrong. Their reckless passion had carried them too far to stop—at least had carried some of them too far; for it is always the savage lads, with their love of cruel excitement, who head the riot—reckless to what bloodshed it may lead. A clog whizzed through the air. Margaret’s fascinated eyes watched its progress; it missed its aim, and she turned sick with affright, but changed not her position, only hid her face on Mr. Thornton’s arm. Then she turned and spoke again:

“For God’s sake! do not damage your cause by this violence. You do not know what you are doing.” She strove to make her words distinct.

A sharp pebble flew by her, grazing forehead and cheek, and drawing a blinding sheet of light before her eyes.

What we love about this passage…

The scene nearly stops us in our tracks with its gripping presentation of politics and violence. The novel, originally published in monthly instalments in Charles Dickens’s magazine Household Words, was read throughout England and America. By focalizing the most pressing issues of the day—liberty, labour, equality—through the conventions of romance, Gaskell was able to draw readers’ sympathies to far-off places and groups of individuals they would never have met in real life, including the Irish labourers who have been forced to come to England in search of work. The title itself—North and South—seems to express the dual foundational ideas of this novel: division and union.

About the Author

Elizabeth Gaskell (1810-1865) was a successful mid-Victorian novelist, writing such well-known works as Mary Barton (1848), Cranford (1851-53), and Ruth (1853). Like Charles Dickens, who published much of her work in his magazine, many of her texts attempted to address the social problems of the day through the conventions of storytelling. She was also an accomplished biographer and wrote The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857)—a work that has attracted controversy ever since for only featuring the most virtuous aspects of Charlotte’s life.

To read alongside…

Why not look in our archive and read some of Gaskell’s contemporaries—Emily Brontë’s haunting poem for one, or perhaps the masterful, spooky opening from her novel Wuthering Heights (1847). Another eerie entry from the period is Margaret Oliphant’s 'The Library Window' (1896).

Suggest a LitHit!

Tell us your own favourites from literature you've read, and we can feature you as a Guest Curator. Just email us with the following information:

Your full name

The title of the book you're suggesting

The location of the excerpt within the book (e.g., "in the middle of chapter 5"), or the excerpt itself copied into the email or attached to it (in Word)

Why you love it, in just a few sentences

About LitHits

LitHits helps you make time for reading by bringing you unabridged excerpts from brilliant literature that you can read on the go, anytime or any place. Our curators carefully select and frame each excerpt so that you can dive right in. We are more than a book recommendation site: we connect you with a powerful, enduring piece of literature, served directly to your mobile phone, tablet or computer.

Today's guest curator...

Dr Daniel Abdalla, core member of LitHits and an expert in nineteenth and twentieth-century literature, particularly its relationship to science.

You might also enjoy...

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on our newsletter:

kshepherdb@yahoo.co.uk

Graphic design by Sara Azmy

All curation content © 2023 LitHits. All rights reserved.