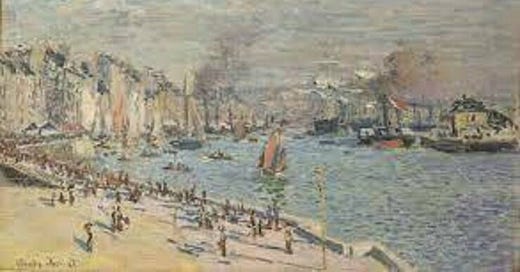

The magic of water

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

Some years ago—never mind how long precisely—having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen and regulating the circulation. Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball. With a philosophical flourish Cato throws himself upon his sword; I quietly take to the ship. There is nothing surprising in this. If they but knew it, almost all men in their degree, some time or other, cherish very nearly the same feelings towards the ocean with me.

...Say you are in the country; in some high land of lakes. Take almost any path you please, and ten to one it carries you down in a dale, and leaves you there by a pool in the stream. There is magic in it. Let the most absent-minded of men be plunged in his deepest reveries—stand that man on his legs, set his feet a-going, and he will infallibly lead you to water, if water there be in all that region. Should you ever be athirst in the great American desert, try this experiment, if your caravan happen to be supplied with a metaphysical professor. Yes, as every one knows, meditation and water are wedded for ever.

But here is an artist. He desires to paint you the dreamiest, shadiest, quietest, most enchanting bit of romantic landscape in all the valley of the Saco. What is the chief element he employs? There stand his trees, each with a hollow trunk, as if a hermit and a crucifix were within; and here sleeps his meadow, and there sleep his cattle; and up from yonder cottage goes a sleepy smoke. Deep into distant woodlands winds a mazy way, reaching to overlapping spurs of mountains bathed in their hill-side blue. But though the picture lies thus tranced, and though this pine-tree shakes down its sighs like leaves upon this shepherd’s head, yet all were vain, unless the shepherd’s eye were fixed upon the magic stream before him. Go visit the Prairies in June, when for scores on scores of miles you wade knee-deep among Tiger-lilies—what is the one charm wanting?—Water—there is not a drop of water there! Were Niagara but a cataract of sand, would you travel your thousand miles to see it? Why did the poor poet of Tennessee, upon suddenly receiving two handfuls of silver, deliberate whether to buy him a coat, which he sadly needed, or invest his money in a pedestrian trip to Rockaway Beach? Why is almost every robust healthy boy with a robust healthy soul in him, at some time or other crazy to go to sea? Why upon your first voyage as a passenger, did you yourself feel such a mystical vibration, when first told that you and your ship were now out of sight of land? Why did the old Persians hold the sea holy? Why did the Greeks give it a separate deity, and own brother of Jove? Surely all this is not without meaning. And still deeper the meaning of that story of Narcissus, who because he could not grasp the tormenting, mild image he saw in the fountain, plunged into it and was drowned. But that same image, we ourselves see in all rivers and oceans. It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life; and this is the key to it all.

What we love about this passage...

These are the opening paragraphs of one of the world's best-known novels, and they follow directly on from its famous opening sentence: 'Call me Ishmael.' To us, Melville not only captures the essence of water's universal appeal, he does so slowly, deliberately, and reflectively, taking time to develop that simple central idea. This brilliantly establishes the pace and tone of the ensuing narrative.

These paragraphs dig deeply into the phenomenon of thalassophilia, the love of the sea. We love the way Melville meditates on this idea, coming at it from various angles and bringing in numerous examples to illustrate that it's so common as to be completely taken for granted.

About the author

Herman Melville (1819-1891) was an American writer, best known for his novels Moby-Dick (1851), The Confidence-Man (1857), and Billy Budd (published posthumously in 1924), all of which take place on water.

To read alongside...

Literature is full of sea-loving authors. One of our favorites is John Masefield's poem 'Sea-Fever', which begins:

'I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by'...

Virginia Woolf's novel The Waves doesn't just describe the sea--the narrative itself is sea-like, with the characters' identities fluidly merging like waves. The narrative of Tove Jansson's The Summer Book similarly bobs along gently, like the water that dominates its island setting. And speaking of islands, Shakespeare's The Tempest is hard to beat for its depiction of shipwrecked sailors wandering around making trouble while the lord of the island, Prospero, wields his magic and enchantment to try to get off its shores.

Henrik Ibsen's play The Lady from the Sea depicts a woman mesmerized by water; when she first appears on stage she is dripping wet from her daily swim in the fjord, and the other characters refer to her as a mermaid. In Monique Roffey's novel The Mermaid of Black Conch (Costa Book of the Year for 2020), we get a startlingly close-up and unromantic look at the body of a living mermaid who has just been caught by some fishermen: webbed hands, barnacles, dreadlocks, sea-lice, and a giant dorsal fin are just some of her remarkable features. The 2018 film The Shape of Water turns the tables on our age-old fascination with mer-people by having a land-bound woman fall in love with a strange, merman-like creature caught by some evil scientists. Look out for a dedicated mermaids newsletter from LitHits one of these days...

Suggest a LitHit!

Tell us your own favourites from literature you've read, and we can feature you as a Guest Curator. Just email us with the following information:

Your full name

The title of the book you're suggesting

The location of the excerpt within the book (e.g., "in the middle of chapter 5"), or the excerpt itself copied into the email or attached to it (in Word)

Why you love it, in just a few sentences

**Please note that we welcome all suggestions but at the moment we can only release excerpts that are out of copyright and in the public domain. This means 75 years or more since the author's death. You can find many such out-of-copyright texts on the internet, for example at Project Gutenberg and Standard Ebooks.

About LitHits

You might also enjoy...

Writers Make Worlds: https://writersmakeworlds.com/

The Ten Minute Book Club: https://www.english.ox.ac.uk/ten-minute-book-club

Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/

Standard Ebooks: https://standardebooks.org/

“Five Tips to Get Reading Again if You’ve Struggled During the Pandemic,” The Conversation (8 January 2021): https://theconversation.com/five-tips-to-get-reading-again-if-youve-struggled-during-the-pandemic-152904

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on our newsletter:

kirsten@lit-hits.co.uk

Graphic design by Sara Azmy

All curation content © 2022 LitHits. All rights reserved.