Hard Times

Immerse yourself in the world of Dickens's dark and furious satire on industrialization and the dangerous idea of Utilitarianism

Charles Dickens, Hard Times

The Story So Far…

In a fictional Victorian mill town, school board Superintendent Thomas Gradgrind runs an experimental school based on the principles of Utilitarianism. He firmly believes the best thing for children is to live by facts and facts alone, rather than emotions; and here he impresses this sense of the world on a new pupil from an equestrian circus-life background, Sissy Jupe.

Now read on…

Thomas Gradgrind, sir. A man of realities. A man of facts and calculations. A man who proceeds upon the principle that two and two are four, and nothing over, and who is not to be talked into allowing for anything over. Thomas Gradgrind, sir—peremptorily Thomas—Thomas Gradgrind. With a rule and a pair of scales, and the multiplication table always in his pocket, sir, ready to weigh and measure any parcel of human nature, and tell you exactly what it comes to. It is a mere question of figures, a case of simple arithmetic. You might hope to get some other nonsensical belief into the head of George Gradgrind, or Augustus Gradgrind, or John Gradgrind, or Joseph Gradgrind (all supposititious, non-existent persons), but into the head of Thomas Gradgrind—no, sir!

In such terms Mr. Gradgrind always mentally introduced himself, whether to his private circle of acquaintance, or to the public in general. In such terms, no doubt, substituting the words ‘boys and girls,’ for ‘sir,’ Thomas Gradgrind now presented Thomas Gradgrind to the little pitchers before him, who were to be filled so full of facts.

Indeed, as he eagerly sparkled at them from the cellarage before mentioned, he seemed a kind of cannon loaded to the muzzle with facts, and prepared to blow them clean out of the regions of childhood at one discharge. He seemed a galvanizing apparatus, too, charged with a grim mechanical substitute for the tender young imaginations that were to be stormed away.

‘Girl number twenty,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, squarely pointing with his square forefinger, ‘I don’t know that girl. Who is that girl?’

‘Sissy Jupe, sir,’ explained number twenty, blushing, standing up, and curtseying.

‘Sissy is not a name,’ said Mr. Gradgrind. ‘Don’t call yourself Sissy. Call yourself Cecilia.’

‘It’s father as calls me Sissy, sir,’ returned the young girl in a trembling voice, and with another curtsey.

‘Then he has no business to do it,’ said Mr. Gradgrind. ‘Tell him he mustn’t. Cecilia Jupe. Let me see. What is your father?’

‘He belongs to the horse-riding, if you please, sir.’

Mr. Gradgrind frowned, and waved off the objectionable calling with his hand.

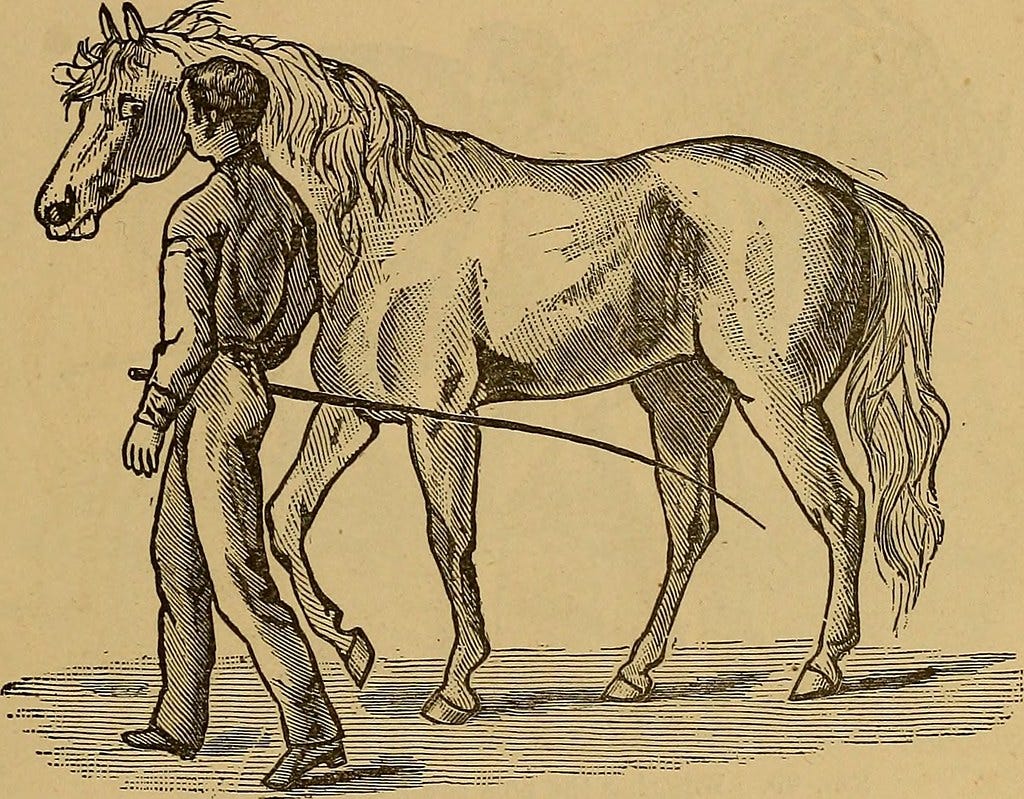

‘We don’t want to know anything about that, here. You mustn’t tell us about that, here. Your father breaks horses, don’t he?’

‘If you please, sir, when they can get any to break, they do break horses in the ring, sir.’

‘You mustn’t tell us about the ring, here. Very well, then. Describe your father as a horsebreaker. He doctors sick horses, I dare say?’

‘Oh yes, sir.’

‘Very well, then. He is a veterinary surgeon, a farrier, and horsebreaker. Give me your definition of a horse.’

(Sissy Jupe thrown into the greatest alarm by this demand.)

‘Girl number twenty unable to define a horse!’ said Mr. Gradgrind, for the general behoof of all the little pitchers. ‘Girl number twenty possessed of no facts, in reference to one of the commonest of animals! Some boy’s definition of a horse. Bitzer, yours.’

The square finger, moving here and there, lighted suddenly on Bitzer, perhaps because he chanced to sit in the same ray of sunlight which, darting in at one of the bare windows of the intensely white-washed room, irradiated Sissy. For, the boys and girls sat on the face of the inclined plane in two compact bodies, divided up the centre by a narrow interval; and Sissy, being at the corner of a row on the sunny side, came in for the beginning of a sunbeam, of which Bitzer, being at the corner of a row on the other side, a few rows in advance, caught the end. But, whereas the girl was so dark-eyed and dark-haired, that she seemed to receive a deeper and more lustrous colour from the sun, when it shone upon her, the boy was so light-eyed and light-haired that the self-same rays appeared to draw out of him what little colour he ever possessed. His cold eyes would hardly have been eyes, but for the short ends of lashes which, by bringing them into immediate contrast with something paler than themselves, expressed their form. His short-cropped hair might have been a mere continuation of the sandy freckles on his forehead and face. His skin was so unwholesomely deficient in the natural tinge, that he looked as though, if he were cut, he would bleed white.

‘Bitzer,’ said Thomas Gradgrind. ‘Your definition of a horse.’

‘Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-four grinders, four eye-teeth, and twelve incisive. Sheds coat in the spring; in marshy countries, sheds hoofs, too. Hoofs hard, but requiring to be shod with iron. Age known by marks in mouth.’ Thus (and much more) Bitzer.

‘Now girl number twenty,’ said Mr. Gradgrind. ‘You know what a horse is.’

She curtseyed again, and would have blushed deeper, if she could have blushed deeper than she had blushed all this time. Bitzer, after rapidly blinking at Thomas Gradgrind with both eyes at once, and so catching the light upon his quivering ends of lashes that they looked like the antennæ of busy insects, put his knuckles to his freckled forehead, and sat down again.

What we love about this passage…

This is Dickens’s only novel set outside of London, and it was also unusual in being originally presented without illustrations. Gradgrind’s school, with its modelling of the ‘best methods’ of education, is one of the structuring forces of this novel, along with the oppressive atmosphere of the industrial town in which the novel is set.

But our amusement at the delicious irony of Gradgrind’s pompousness is tempered by attention to the other figures in this scene, especially in the extraordinary paragraph describing Sissy and Bitzer in the ray of sunshine—one fair, the other dark-haired, both transformed in that moment from what they factually are to how the light makes them seem. ‘Facts’ give way to impressions, imagination, flights of fancy; and the delightful paradox is that light—often a metaphor for education and (literally) enlightenment—threatens to undermine Gradgrind’s educational methods and show us a better, healthier way to learn.

The narrative steals his thunder, but only for a moment. The bewildered Sissy is humiliated by her encounter with an unfamiliar system that privileges rote-learned taxonomical facts over her lived knowledge of horses. The bleached, quivering Bitzer embodies the fading of personality, vivacity and inner light from children subjected to a rigid system of education without creativity, imagination, empathy, and leisure.

Leisure in Dickens’s world meant performance, and in the next chapter, Gradgrind’s own children are discovered attending the circus—the antithesis of his grim teachings and a contrasting source of joy and humanity throughout the novel.

About the Author…

Charles Dickens (1812-70) was the author of many best-sellers of the Victorian period including A Christmas Carol, Bleak House, Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, A Tale of Two Cities, and David Copperfield.

In the 1850s, Dickens established and edited the weekly periodical, Household Words, published every Saturday from March 1850 to May 1859 (at a cost of tuppence). This was the work in which Hard Times was serialised in the Spring and Summer of 1854.

To Read Alongside…

Elizabeth Gaskell also published some of her novels in serial form through Household Words: Cranford, My Lady Ludlow, North and South. The latter is featured here in our newsletter ‘Strike!’

We also have past newsletters featuring Dickens’s work, such as Bleak House and Great Expectations.

Suggest a LitHit!

Tell us your own favourites from literature you've read, and we can feature you as a Guest Curator if you like. Just email us with the following information:

Your full name

The title of the book you're suggesting

The location of the excerpt within the book (e.g., "in the middle of chapter 5"), or the excerpt itself copied into the email or attached to it (in Word)

Why you love it, in just a few sentences

About LitHits

LitHits helps you make time for reading by bringing you unabridged excerpts from brilliant literature that you can read on the go, anytime or any place. Our curators carefully select and frame each excerpt so that you can dive right in. We are more than a book recommendation site: we connect you with a powerful, enduring piece of literature, served directly to your mobile phone, tablet or computer.

You might also enjoy...

Feedback

We'd love to hear your thoughts on our newsletter:

kshepherdb@yahoo.co.uk

Graphic design by Sara Azmy

All curation content © 2024 LitHits. All rights reserved.